Balance Mastery - Crafting Your Gut-Healthy Exercise Regimen(Part 2/4)

Harmonizing Intensity, Frequency, Duration, Timing, and Personalization

Welcome back to our exciting journey of discovering the power of exercise and gut health! In Part 1, we dove deep into the science behind the connection between exercise and our gut microbiome, discussed exercise resistance, and explored strategies to overcome barriers. Now, it's time to take our newfound knowledge to the next level.

Part 2

In Part 2, we'll master the art of balance as we embark on crafting our very own gut-healthy exercise regimen. Together, we'll uncover the secrets of intensity, frequency, duration, timing, and circadian rhythms, and learn how to tailor a personalized fitness plan that works in harmony with our unique needs and preferences. So, let's get ready to strike the perfect balance and pave the way for a healthier, happier gut!

Exercise Intensity, Frequency, Duration, Timing, and Time of the day: Finding the Balance

We recognize the importance of finding the right balance of exercise intensity, frequency, duration, timing, and time of day for optimal gut health.

Exercise intensity refers to the level of effort put into physical activity, and it is usually measured using heart rate or perceived exertion. High-intensity exercise can be beneficial for gut health by improving gut motility and reducing inflammation, but it is essential to start gradually and work up to higher intensities to avoid injury and overexertion.

Exercise frequency refers to the number of times per week that an individual engages in physical activity. Regular exercise is necessary for optimal gut health, and a minimum of 150 minutes of moderate-intensity exercise per week is recommended. However, the frequency of exercise may depend on an individual's health status, goals, and lifestyle.

Exercise duration refers to the length of time an individual spends engaged in physical activity. The recommended duration of exercise is 30-60 minutes per session, but this may vary based on an individual's fitness level, health status, and goals.

Exercise timing refers to the optimal time of day to engage in physical activity. Morning exercise may be beneficial for gut health, as it has been shown to improve gut motility and reduce inflammation. However, the best time of day to exercise may depend on our schedule, preferences, and other factors such as work, family, and social commitments.

Finally, the time of day at which one eats before or after exercise can also impact gut health. Eating too close to exercise can cause discomfort and potentially harm gut health, while consuming a meal or snack containing carbohydrates and protein before or after exercise can provide energy and nutrients necessary for optimal gut health.

In conclusion, finding the right balance of exercise intensity, frequency, duration, timing, and time of day is crucial for optimal gut health. It is essential to start gradually, listen to the body's signals, and work with a professional to design an exercise program that meets individual needs and goals while also promoting gut health.

A. The impact of exercise intensity on gut health

1. Benefits of moderate-intensity exercise

2. Potential drawbacks of high-intensity exercise

We recognize the importance of understanding the relationship between exercise intensity and gut health. In this essay, we will discuss the benefits of moderate-intensity exercise and the potential drawbacks of high-intensity exercise on gut health.

The Impact of Exercise Intensity on Gut Health

A.1. Benefits of Moderate-Intensity Exercise

1.1. Improved gut microbiota composition

Moderate-intensity exercise positively influences gut microbiota by increasing the diversity and abundance of beneficial bacteria, leading to better immune function, reduced inflammation, and enhanced digestion and nutrient absorption (Mailing et al., 2019).

1.2. Increased production of short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs)

Regular moderate exercise stimulates the production of SCFAs such as butyrate, propionate, and acetate, which play a crucial role in maintaining gut health by providing energy to gut epithelial cells, regulating inflammation, and promoting the growth of beneficial bacteria (Sivaprakasam et al., 2016).

1.3. Enhanced gut barrier function

Moderate-intensity exercise can improve gut barrier function by increasing the expression of tight junction proteins, which maintain the integrity of the gut lining, reducing the risk of harmful substances leaking into the bloodstream and causing inflammation or other issues (Lambert, 2018).

1.4. Reduced stress and anxiety

Engaging in moderate exercise can help reduce stress and anxiety, which can negatively impact gut health. Stress has been shown to alter the gut microbiome, increase gut permeability, and contribute to inflammation (Foster et al., 2017).

A.2. Potential Drawbacks of High-Intensity Exercise

2.1. Increased risk of gastrointestinal distress

High-intensity exercise can increase the risk of gastrointestinal distress, including symptoms like nausea, abdominal cramping, diarrhea, and reflux. This is likely due to a combination of factors, such as reduced blood flow to the gut, increased gut permeability, and the release of stress hormones (Costa et al., 2017).

2.2. Negative impact on gut microbiota

Excessive high-intensity exercise may negatively impact gut microbiota, potentially reducing the abundance of beneficial bacteria and increasing the abundance of potentially harmful bacteria. This can disrupt the balance of the gut ecosystem, leading to inflammation and other health issues (Mach et al., 2017).

2.3. Compromised gut barrier function

Prolonged, high-intensity exercise can compromise gut barrier function by increasing the permeability of the gut lining, allowing harmful substances to enter the bloodstream. This can lead to systemic inflammation and potentially increase the risk of illness and chronic disease (van Wijck et al., 2012).

II. The Importance of Exercise Frequency and Consistency

B.1. Maintaining a healthy gut microbiota

Consistent and frequent exercise is crucial for promoting a diverse and balanced gut microbiota. Regular exercise has been shown to increase the abundance of beneficial bacteria and reduce the presence of harmful bacteria, contributing to a healthier gut ecosystem (Mailing et al., 2019).

B.2. Sustained production of short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs)

Frequent and consistent exercise promotes the sustained production of SCFAs such as butyrate, propionate, and acetate. These SCFAs play a critical role in gut health by providing energy to gut epithelial cells, regulating inflammation, and supporting the growth of beneficial bacteria (Sivaprakasam et al.,B.3. Improved gut barrier function

Regular exercise helps maintain gut barrier function by increasing the expression of tight junction proteins and decreasing gut permeability. A consistent exercise routine helps preserve the integrity of the gut lining, reducing the risk of harmful substances entering the bloodstream and causing inflammation (Lambert, 2018).

B.4. Stress reduction

Engaging in frequent and consistent exercise helps reduce stress and anxiety, which can negatively impact gut health. Exercise has been shown to mitigate the effects of stress on the gut microbiome, gut permeability, and inflammation (Foster et al., 2017).

III. Optimal Duration of Exercise Sessions for Gut Health

C.1. Balancing intensity and duration

Research suggests that a balance between exercise intensity and duration is vital for gut health. Moderate-intensity exercise sessions lasting between 30 and 60 minutes have been shown to produce the most favorable effects on gut health, including improved gut microbiota composition, enhanced gut barrier function, and increased SCFA production (Mailing et al., 2019).

C.2. Avoiding excessive duration

Excessively long exercise sessions, particularly at high intensity, may lead to gastrointestinal distress and compromised gut health. Prolonged exercise can increase gut permeability and negatively impact gut microbiota composition (Costa et al., 2017). Therefore, it is essential to find an individualized balance between exercise duration and intensity to optimize gut health.

Conclusion

Exercise intensity, frequency, consistency, and duration all play critical roles in promoting gut health. Moderate-intensity exercise offers various benefits for gut health, while high-intensity exercise has potential drawbacks. Frequent and consistent exercise contributes to a healthy gut microbiota, sustained production of SCFAs, improved gut barrier function, and stress reduction. The optimal duration of exercise sessions for gut health appears to be between 30 and 60 minutes of moderate-intensity exercise. It is crucial to find an individualized balance between exercise parameters to maintain optimal gut health.

References

Costa, R. J. S., Snipe, R. M. J., Kitic, C. M., & Gibson, P. R. (2017). Systematic review: exercise-induced gastrointestinal syndrome—implications for health and intestinal disease. Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics, 46(3), 246-265.

Foster, J. A., Rinaman, L., & Cryan, J. F. (2017). Stress & the gut-brain axis: Regulation by the microbiome. Neurobiology of Stress, 7, 124-136.

Lambert, G. P. (2018). Stress-induced gastrointestinal barrier dysfunction and its inflammatory effects. Journal of Animal Science, 88(4), 16-28.

Mach, N., Fuster-Botella, D. (2017). Endurance exercise and gut microbiota: A review. Journal of Sport and Health Science, 6(2), 179-197.

Mailing, L. J., Allen, J. M., Buford, T. W., Fields, C. J., & Woods, J. A. (2019). Exercise and the gut microbiome: a review of the evidence, potential mechanisms, and implications for human health. Exercise and Sport Sciences Reviews, 47(2), 75-85.

Sivaprakasam, S., Prasad, P. D., & Singh, N. (2016). Benefits of short-chain fatty acids and their receptors in inflammation and carcinogenesis. Pharmacology & Therapeutics, 164, 144-151.

van Wijck, K., Lenaerts, K., Grootjans, J., Wijnands, K. A., Poeze, M., van Loon, L. J., Dejong, C. H., & Buurman, W. A. (2012). Physiology and pathophysiology of splanchnic hypoperfusion and intestinal injury during exercise: strategies for evaluation and prevention. American Journal of Physiology-Gastrointestinal and Liver Physiology, 303(2), G155-G168.

We understand that different people will be at different fitness levels and also goals may be different. So, it’s important to tailor our exercises based on our personal situation. Let’s walk through some of the ideas to personalize exercise and tailor to our needs.

Personalizing Exercise for Gut Health: Tailoring Your Program

A. Assessing personal fitness levels and goals

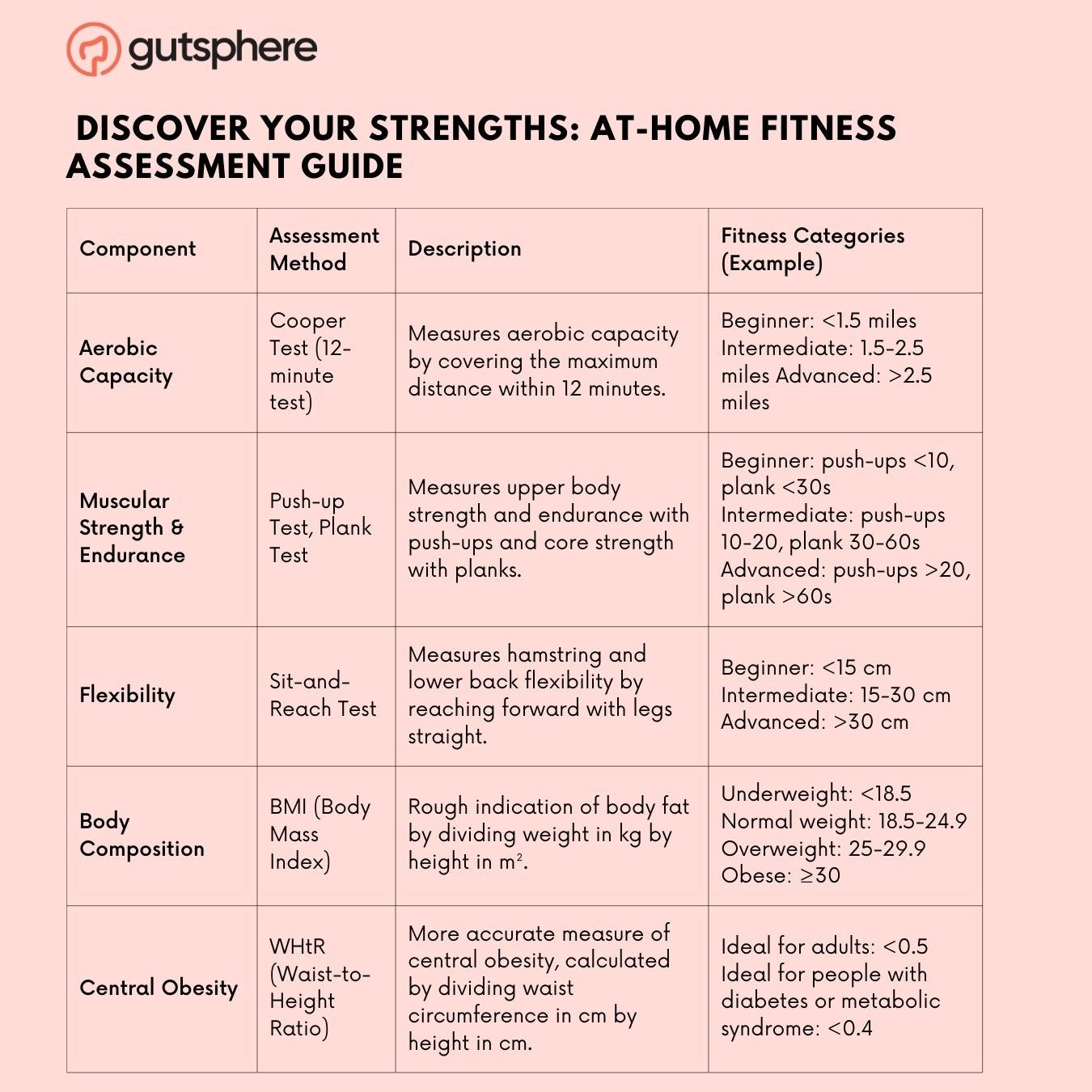

An essential first step in personalizing an exercise program is conducting a baseline fitness assessment. We can evaluate our fitness levels across various components using the following methods:

Aerobic Capacity: We can measure our aerobic capacity through a submaximal exercise test, such as the 12-minute Cooper Test, where we aim to cover the maximum distance possible by walking or running within the given time.

Muscular Strength and Endurance: We can perform a push-up test and a plank test to measure upper body strength and endurance. The number of push-ups we can do without stopping and the duration we can hold a plank position are both useful indicators.

Flexibility: We can use the sit-and-reach test to measure our flexibility. Sit on the floor with our legs straight, and reach forward as far as possible while keeping our knees extended.

Body Composition: We can calculate our body mass index (BMI) by dividing our weight in kilograms by our height in meters squared. While not a direct measurement of body fat, BMI can provide a rough indication of whether we are underweight, normal weight, overweight, or obese.

waist-to-height ratio (WHtR): WHtR is calculated by dividing our waist circumference in centimeters by our height in centimeters. A high WHtR is associated with an increased risk of heart disease, stroke, type 2 diabetes, and metabolic syndrome. The ideal WHtR for adults is less than 0.5. For people with diabetes or metabolic syndrome, the ideal WHtR is less than 0.4.

WHtR is a more accurate measure of central obesity than BMI. Central obesity is a risk factor for heart disease, stroke, type 2 diabetes, and metabolic syndrome. WHtR is also a better predictor of mortality than BMI.

We mentioned a few tests such as the cooper test, push up test and plank test, sit and reach test for aerobic, strength, and flexibility fitness test simultaneously. Although we won't go into details about many different tests we can do. We do want to explain the tests we mentioned above.

Cooper Test: The Cooper Test is a widely used fitness assessment tool designed to estimate an individual's aerobic capacity or VO2 max (maximum oxygen uptake). The test requires participants to run, jog, or walk as far as possible within 12 minutes. The total distance covered in the 12-minute period is then compared to standardized norms to determine the individual's aerobic fitness level. The Cooper Test is a simple and effective way to measure cardiovascular endurance, as it closely correlates with VO2 max.

Push-up Test: The push-up test is a common method to assess upper body muscular strength and endurance. To perform the test, the participant assumes the standard push-up position, with hands shoulder-width apart and feet together. The participant then performs as many push-ups as possible while maintaining proper form, which includes keeping the body straight and lowering the chest to within a few inches of the ground. The test continues until the participant is unable to maintain proper form or is unable to complete another repetition. The total number of correctly performed push-ups is recorded and compared to age- and sex-specific norms to determine the individual's muscular strength and endurance.

Plank Test: The plank test is a popular assessment tool to evaluate core strength and endurance. To perform the test, the participant assumes the plank position, with forearms on the ground, elbows aligned below the shoulders, and feet hip-width apart. The body should form a straight line from the head to the heels, and the participant must hold this position for as long as possible. The test is terminated when the participant can no longer maintain proper form or is unable to continue. The total time held in the plank position is recorded and compared to age- and sex-specific norms to determine the individual's core strength and endurance.

Sit-and-Reach Test: The sit-and-reach test is a widely used assessment tool to evaluate hamstring and lower back flexibility. To perform the test, the participant sits on the ground with legs fully extended and feet placed against a sit-and-reach box or a yardstick taped to the floor. The participant then reaches forward as far as possible with both hands while keeping the legs straight and the knees together. The distance reached by the fingertips is recorded, and the test is usually performed three times. The best of the three attempts is compared to age- and sex-specific norms to determine the individual's flexibility.

Furthermore, we mentioned tests without devices or any professional observations. These days many smartwatches and fitness trackers provide VO2 max and we can go to professionals to get our more accurate fitness level. However, these zero costs at home tests can provide us with our close to accurate ballpark scores. And most of the time, that should be sufficient to help us classify ourselves.

Based on the results of these assessments, we can be classified into different fitness categories, for example:

Beginner: Cooper Test <1.5 miles, push-ups <10, plank <30 seconds, sit-and-reach <15 cm

Intermediate: Cooper Test 1.5-2.5 miles, push-ups 10-20, plank 30-60 seconds, sit-and-reach 15-30 cm

Advanced: Cooper Test >2.5 miles, push-ups >20, plank >60 seconds, sit-and-reach >30 cm

And these assessments can help us set up smart goals. Below is an example.

Setting SMART goals

Set specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, and time-bound (SMART) goals to guide your exercise program. For example:

Beginner: Improve gut health by engaging in moderate-intensity exercise for 30 minutes, three times per week for three months.

Intermediate: Improve gut health by increasing moderate-intensity exercise duration to 45 minutes, four times per week for three months.

Advanced: Improve gut health by maintaining 60 minutes of moderate-intensity exercise, five times per week for three months.

And we can periodically conduct those tests to measure our progress.

Furthermore, we are cognizant, some of us may have physical limitations and medical considerations. In those cases, we can modify our exercises based on our conditions.

Identifying Physical Limitations and Medical Considerations

B.1. Screening for Physical Limitations and Medical Conditions

Before starting a new exercise program, it is essential to identify any physical limitations or medical conditions that may impact your exercise choices. A self-assessment or consultation with a healthcare professional can help you identify these limitations. Use the Physical Activity Readiness Questionnaire (PAR-Q) as a starting point.

The Physical Activity Readiness Questionnaire (PAR-Q) is a simple, self-administered screening tool used to determine our readiness to engage in physical activity or exercise programs. It is designed to identify individuals who may have health conditions or risk factors that could potentially increase the risk of adverse events during exercise. The PAR-Q helps to ensure that we can safely participate in physical activity and assists fitness professionals and healthcare providers in recommending appropriate exercise programs.

The PAR-Q consists of a series of questions related to our current health status, medical history, and any symptoms or signs that might indicate a potential risk during physical activity. Questions may include inquiries about chest pain, dizziness, joint problems, high blood pressure, and other health concerns. We answer each question with a "yes" or "no" response.

To use the PAR-Q:

Obtain a copy of the questionnaire. Here is a simplified version of the PAR-Q:

a. Has a doctor ever said that we have a heart condition and recommended only medically supervised physical activity?

b. Do we feel pain in our chest during physical activity?

c. In the past month, have we experienced chest pain when not engaged in physical activity?

d. Do we lose balance due to dizziness or have we ever lost consciousness?

e. Do we have a bone or joint problem that could be made worse by physical activity?

f. Has a doctor ever prescribed medication for our blood pressure or a heart condition?

g. Are we aware of any other reason why we should not engage in physical activity?

Read each question carefully and provide an honest answer, selecting either "yes" or "no."

Review our responses after completing the questionnaire.

If we answered "no" to all the questions, it is generally considered safe for us to engage in physical activity, and we can proceed with starting an exercise program. However, it is still recommended to consult with a healthcare professional, especially if we are new to exercise or have specific health concerns.

If we answered "yes" to any of the questions, we should consult with a healthcare professional before beginning an exercise program. They will help to determine if there are any precautions or modifications needed for us to participate safely in physical activity. In some cases, further evaluation or medical clearance may be necessary.

Keep in mind that the PAR-Q is a screening tool and not a diagnostic tool. It is always important to consult with healthcare professionals for personalized advice and guidance related to our health and exercise participation.

B.2. Adapting Exercises Based on Limitations and Conditions

Adapting exercises based on limitations and conditions is crucial for ensuring that we can participate safely and effectively in physical activities while addressing our unique needs. By making appropriate modifications, we can reduce the risk of injury, improve overall performance, and achieve our fitness goals.

Here are some general guidelines for adapting exercises based on specific limitations and conditions:

Joint pain or arthritis:

Choose low-impact activities like swimming, water aerobics, cycling, or walking to reduce stress on the affected joints.

Incorporate range-of-motion exercises to maintain joint flexibility and mobility.

Use resistance bands or machines for strength training to control resistance and protect joints.

Back pain:

Focus on core-strengthening exercises to improve posture and provide better support for the spine.

Avoid exercises that place excessive stress on the lower back, such as heavy deadlifts or improper sit-ups.

Incorporate stretching exercises targeting the hamstrings, hip flexors, and lower back muscles to improve flexibility.

Heart conditions:

Begin with low- to moderate-intensity aerobic activities, gradually increasing intensity under medical supervision.

Include regular breaks and monitor heart rate to ensure it stays within a safe range.

Avoid high-intensity or competitive activities without prior medical clearance and supervision.

Asthma:

Choose activities that allow for regular breaks and breathing control, such as yoga or swimming.

Warm-up and cool-down properly to minimize exercise-induced asthma symptoms.

Monitor air quality and exercise indoors on days with poor air quality or extreme temperatures.

Obesity:

Start with low-impact, moderate-intensity aerobic activities, such as walking or water aerobics, to reduce stress on joints.

Gradually increase the duration and frequency of exercise sessions.

Incorporate strength training to improve muscle mass and metabolic function.

Diabetes:

Engage in regular aerobic activities, such as walking or cycling, to help manage blood glucose levels.

Incorporate strength training to improve insulin sensitivity and overall blood glucose management.

Monitor blood glucose levels before, during, and after exercise and make necessary adjustments to prevent hypoglycemia.

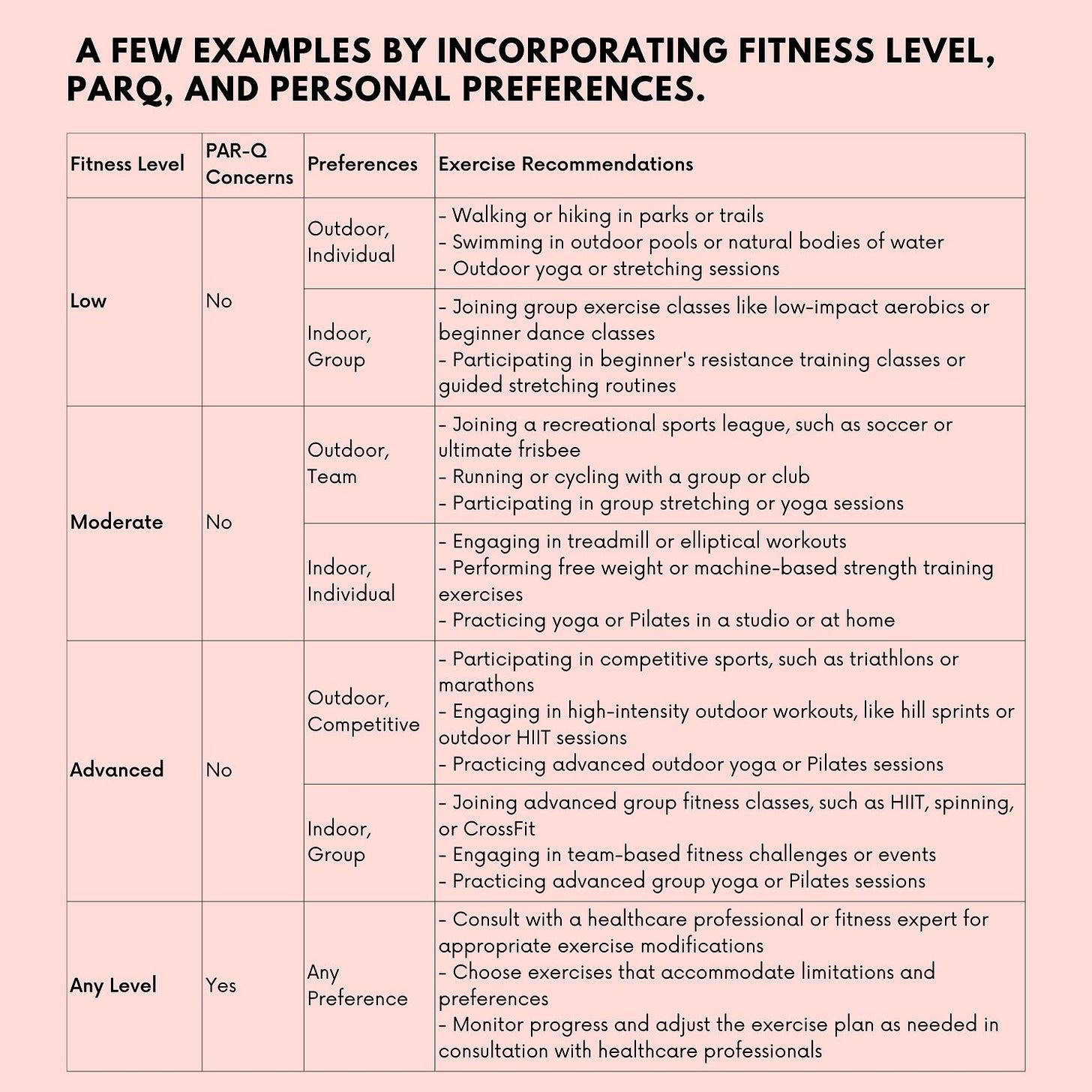

C. Incorporating Individual Preferences and Interests

C.1. Identifying Preferred Activities

To select activities that are enjoyable and promote adherence, we should consider our interests and preferences. Ask ourselves the following questions:

Do we prefer indoor or outdoor activities?

Are we more interested in individual or group activities?

Do we enjoy competitive sports or recreational activities?

What types of exercise or physical activities have we enjoyed in the past?

C.2. Creating a Personalized Exercise Plan Based on Preferences

Based on our interests and preferences, we can create a personalized exercise plan that incorporates a variety of activities to keep us engaged and promote gut health. Here are some examples of personalized plans based on different preferences:

Indoor enthusiast:

Join a local gym and participate in group exercise classes like yoga, Pilates, or dance fitness.

Incorporate resistance training, such as free weights or machine exercises, and indoor cycling to maintain a diverse routine.

Try different gym equipment, like treadmills, ellipticals, or rowing machines, to add variety to your workouts.

Outdoor lover:

Combine outdoor activities like hiking, cycling, and swimming with flexibility exercises like outdoor yoga or tai chi.

Explore local parks, trails, or open spaces for walking, jogging, or other outdoor exercises.

Try new outdoor activities, such as stand-up paddleboarding, kayaking, or rock climbing, to challenge yourself and maintain motivation.

Team player:

Join a recreational sports league like soccer, basketball, or volleyball.

Balance team activities with individual exercises like running or strength training.

Participate in group fitness challenges or events, such as charity runs, obstacle course races, or team-based fitness competitions.

Solo exerciser:

Create a home workout routine that incorporates bodyweight exercises, resistance bands, or home gym equipment.

Follow online workout programs or apps that cater to your interests and preferences.

Incorporate mindfulness-based activities like yoga or meditation to enhance overall well-being and support gut health.

Remember that it's essential to include a balance of aerobic, strength, and flexibility exercises in our personalized plan to promote overall health and support gut health. We should also consider adjusting our exercise routine over time to prevent boredom and accommodate any changes in our fitness level or lifestyle.

We've covered a lot of ground in our journey so far. We've learned how to achieve balance in our exercise routines, and we've discovered the importance of personalizing our gut-healthy exercise plans. But what if we told you that there's more to this fascinating story?

Next

As we prepare for Part 3, we'll dive into the world of fitness fusion, where exercise, nutrition, and stress management unite to create a powerful impact on our gut microbiome. Together, we'll explore the benefits of exercise diversity, understand the synergy between nutrition and physical activity, and delve into the intriguing dynamics between exercise, stress, and gut health.

Stay tuned, as our journey into the exciting realm of gut health and fitness continues! In Part 3, we'll uncover even more groundbreaking insights and practical tips to help us elevate our well-being to new heights. Let's keep pushing forward and unlock the full potential of our gut health!

Request

Share

Our sincere request to you is to share the newsletter with your friends, family, and community so that they can benefit from the content. Also it will help us grow the newsletter, and eventually, as we release more content, digital tools, and more we will enable people around the world to live chronic disease free.

Subscribe

If you haven’t already subscribed then our sincere request, please subscribe.

Feedback

Also, please give us feedback so that we can improve the content. And if there are any topics that you want us to cover please send us your questions and topics. Furthermore, if you try any of the things we provided information please share your experience with us.

Thank You

gutsphere Team

Disclaimer

Please note that the information provided in this newsletter is for informational purposes only and should not be considered as a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. If you have any concerns or questions about our health, please consult with a licensed healthcare professional. The information contained in this newsletter is not intended to diagnose, treat, cure, or prevent any disease. The publisher and authors of this newsletter assume no responsibility for any adverse effects that may result from the use of the information contained herein.